Setup : Channel coding

We consider the problem of reliably communicating a binary message over a noisy channel. The effect of noise can be mitigated by adding redundancy to the message. One simple method to achieve this is through repetition coding, where the same bit is sent multiple times; and we can reliably decode the bit through a majority vote. This process is known as channel coding, which involves an encoder that converts messages into higher-dimensional codewords, and a decoder that retrieves the original message from the noisy codewords, as depicted in the figure below. An \((n,k)\) code maps \(k\) messages to a codeword of size \(n\). Over the years, numerous codes have been invented, including convolutional codes, turbo codes, LDPC codes, and more recently, polar codes. The impact of these codes has been tremendous; each of these codes have been part of global communication standards, and have powered the information age. At large blocklengths, these schemes operate close to information-theoretic limits. However, there is still room for improvement in the short-to-medium blocklength regime. The invention of codes has been sporadic, and primarily driven by human ingenuity. Recently, deep learning has achieved unparalleled success in a wide range of domains. We explore ways to automate the process of inventing codes using deep learning.

Figure 1: Channel coding

Deep-Learning-based Channel codes

The search for good codes can be automated by parameterizing and learning both the encoder and decoder using neural networks. However, constructing effective non-linear codes using this approach is highly challenging: in fact, naively using off-the-shelf neural architectures often results in performance worse than even repetition codes.

Nevertheless, several recent works have introduced neural codes that match or outperform classical schemes. A common theme is the incorporation of structured redundancy, by using principled coding-theoretic encoding and decoding structures. For example, Turbo Autoencoder [2] uses sequential encoding and decoding along with interleaving of input bits, inspired by Turbo codes. KO codes [3] generalizes Reed-Muller encoding and Dumer decoding by replacing selected components in the Plotkin tree with neural networks. Product Autoencoder [4] generalizes two-dimensional product codes to scale neural codes to larger block lengths. In this post, we introduce DeepPolar [1], which generalizes the coding structures of large-kernel Polar codes by using non-linear kernels parameterized by NNs.

Polar codes

Polar codes, devised by Erdal Arikan in 2009, marked a significant breakthrough as the first class of codes with a deterministic construction proven to achieve channel capacity, via successive cancellation decoding. Further, in conjunction with higher complexity decoders, these codes also demonstrate good finite-length performance while maintaining relatively low encoding and decoding complexity. The impact of Polar codes is evident from their integration into 5G standards within just a decade of their proposal—a remarkably swift timeline (typically, codes take several decades to be adopted into cellular standards).

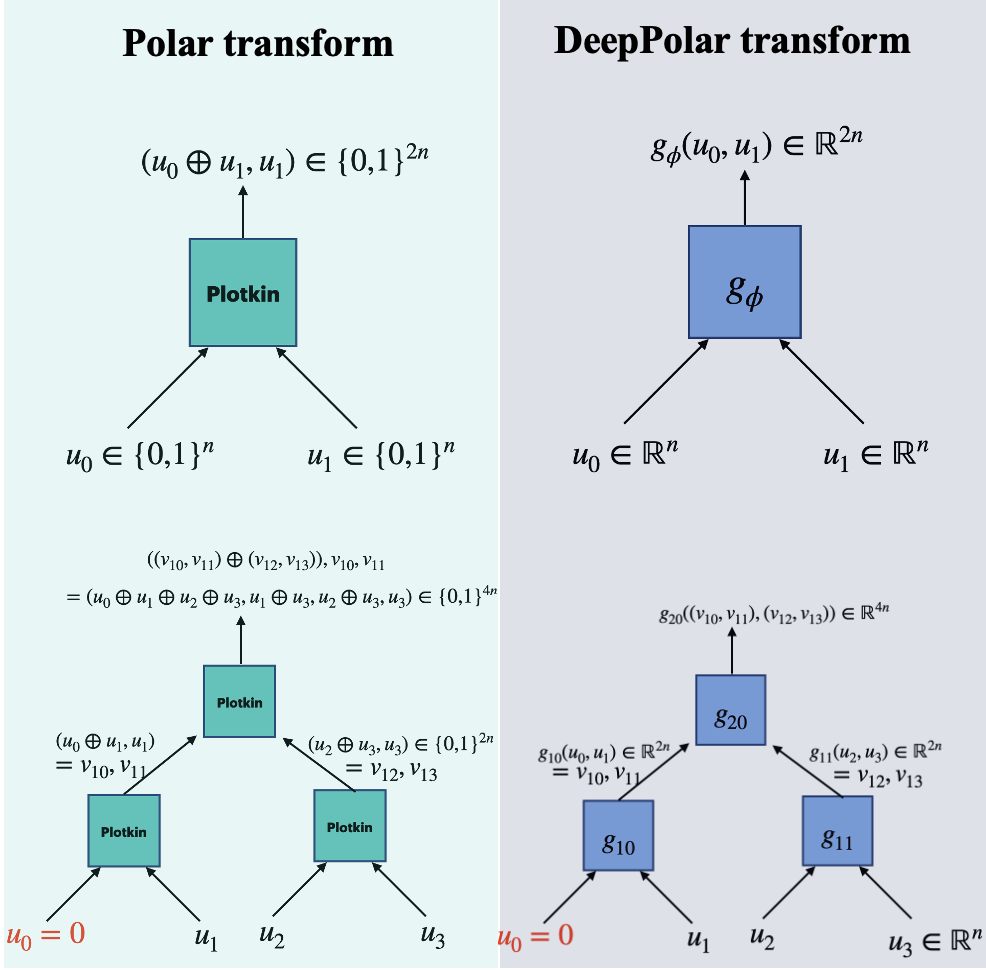

An efficient way to view Polar encoding is via the Plotkin transform : \(\{0,1\}^d \times \{0,1\}^d \to \{0,1\}^{2d}\), which transforms \((u_0, u_1) \to (u_0 \oplus u_1, u_1)\). This Plotkin transform is applied recursively on a tree to obtain the full Polar transform. This recursive application leads to a fascinating phenomenon called “channel polarization” - where each input bit encounters either a noiseless or highly noisy channel under successive cancellation decoding. This selective reliability allows us to transmit message bits through reliable positions only, while “freezing” less reliable positions with a known value, typically zero.

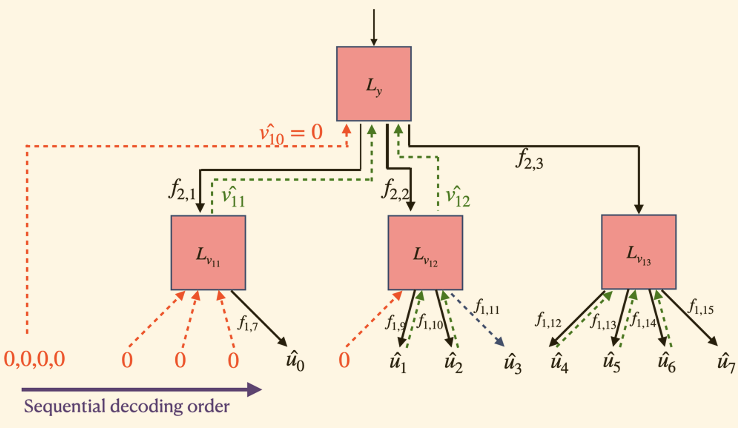

Polar codes can be decoded efficiently using the Successive Cancellation (SC) decoder. The basic principle behind the SC algorithm is to sequentially decode each message bit \(u_i\) according to the conditional likelihood given the corrupted codeword \(y\) and previously decoded bits \(\hat{\mathbf{u}}^{(i-1)}\). The LLR for the \(i^{\text{th}}\) bit can be computed as \begin{equation} L_i = \log \left( \frac{\mathbb{P}(u_i = 0 \mid y, \hat{\mathbf{u}}^{(i-1)})}{\mathbb{P}(u_i = 1 \mid y, \hat{\mathbf{u}}^{(i-1)})} \right). \end{equation}

A detailed exposition of Polar coding and decoding can be found in these notes.

DeepPolar codes

To learn a code, i.e., an encoder-decoder pair, we need to choose an appropriate parameterization. It turns out that off-the-shelf neural architectures perform poorly on this task, primarily due to the curse of dimensionality. For example, consider a scenario where we must map \(k=37\) distinct messages into a 256-dimensional codeword space. This involves learning \(2^{37}\) codewords in a 256-dimensional space. During training, only a tiny fraction of these messages are observed, which without strong inductive biases leads to poor generalization to unseen messages.

One way to address this problem, is to use structured redundancy by the use of principled coding-theoretic structures to design our neural architecture. DeepPolar codes use a neural architecture that generalizes the encoding and decoding structures of Polar codes. Our major innovations are the following:

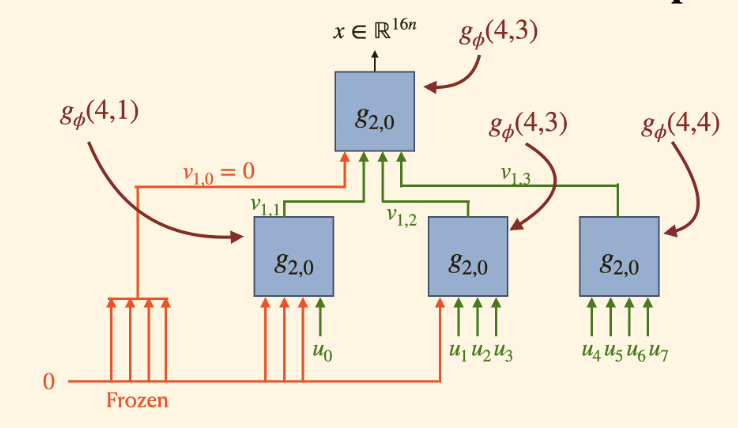

1) Kernel Expansion: The conventional \(2 \times 2\) Polar kernel is expanded into a larger \(\ell \times \ell\) kernel. 2) Learning the kernel: We parameterize each kernel by a learnable function \(g_\phi\), represented by a small Multilayer Perceptron (MLP). Likewise, we augment the SC decoder with learnable functions \(f_\theta\). The encoder-decoder pair is trained jointly to minimize the bit error rate (BER).

Figure 2: DeepPolar maintains the structure of Polar codes, while generalizing the Plotkin transform

The expanded function space afforded by the non-linearity and the increased kernel size allows us to discover more reliable codes within the neural Plotkin code family. Our experiments show that setting kernel size \(\ell = \sqrt{n}\) yields the best performance. This finding is consistent with the principles of the bias-variance tradeoff; while larger kernel provide expanded function spaces, it is harder to generalize with limited training examples. As shown in Figure 3a and 3b, DeepPolar maintains the Polar encoding and decoding structures; this inductive bias allows effective generalization to the full message sapce.

Figure 3: DeepPolar encoder (top) and decoder (bottom) for ($n=16, k=7, \ell=4$)

Notably, DeepPolar codes map binary messages directly to the real field. This can be seen as joint coding + modulation; this approach opens up new avenues to custom-design application-specific communication systems.

Training

Now that we have chosen the neural architecture, we move to designing an effective training procedure. The reliability of a code is typically assessed using metrics like the Bit Error Rate (BER) and the Block Error Rate (BLER), which measure the fraction of bits and codewords received incorrectly, respectively. However, since these metrics are not differentiable, we use binary cross entropy between transmitted and estimated messages as a surrogate loss function to the BER.

Some important training considerations include : 1) Alternating training: To avoid getting stuck in local optima, we train the encoder and decoder seperately, in an alternating fashion. 2) Batch size: Employing a large batch size is essential for stabilizing the training process. Larger batches help average out the effects of the noisy channel, providing a more consistent gradient for updates and reducing variance. 3) Training SNR: The choice of Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) during training is key to ensure robust generalization to various noise conditions. Using the same SNR during training and test time is often sub-optimal. Intuitively, training on a high SNR encounters error events very rarely, leading to poor learning; while training at a very low SNR is tantamount to learning from noise. Instead, training on a range of SNRs where samples lie close to the decision boundary proves effective. 4) For DeepPolar codes, we employ a curriculum training procedure that exploits the polar structure of the codes. Initially, each kernel is pretrained individually (Stage 1). Following this, we use these pretrained kernels to initialize the encoder and decoder (Stage 2). This staged training leads to faster convergence to better optima.

Results

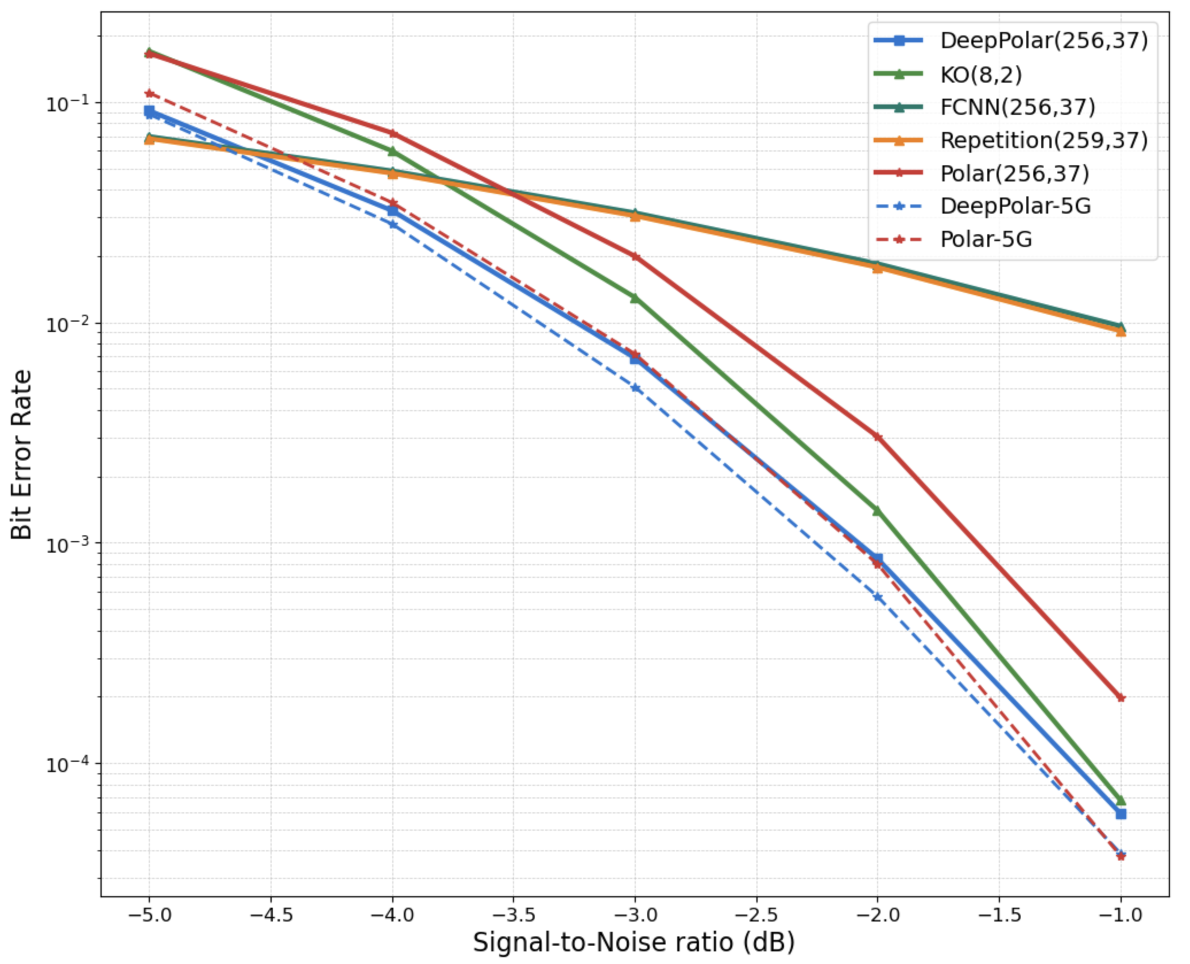

We choose the Bit Error Rate (BER), as our evaluation metric. Figure 4 compares the BER performance of DeepPolar with various schemes. Firstly, we note that a code learned by naive parameterization, eg via a fully connected neural network (FCNN) fails to beat even the simple repetition codes. In contrast, DeepPolar (blue) shows significant gains in BER compared to Polar codes (red) under succesive cancellation decoding.

Figure 4: BER performance of DeepPolar($n=256, k=37, \ell=16$)

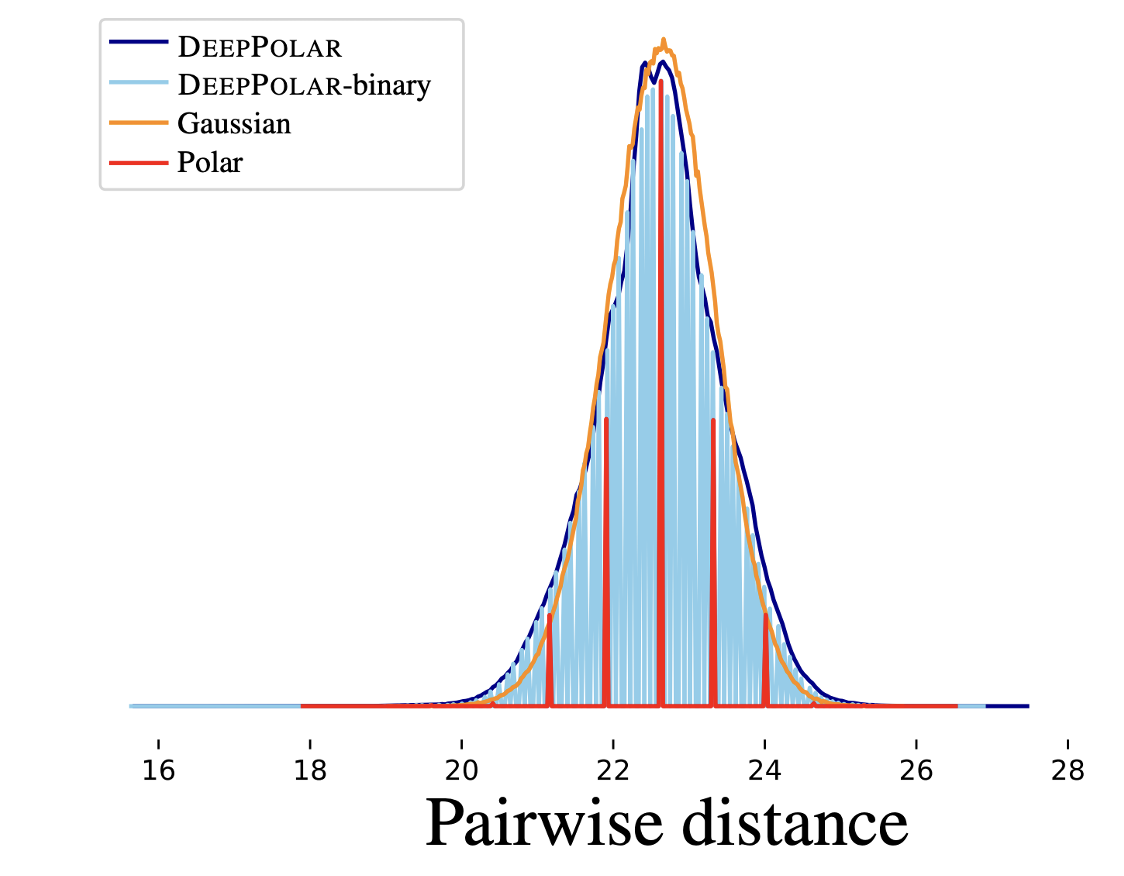

To interpret the encoder, we examine the distribution of pairwise distances between codewords. Gaussian codebooks achieve capacity and are optimal asymptotically (Shannon, 1948). Remarkably, the distribution of DeepPolar codewords closely resembles that of the Gaussian codebook. This is an encouraging sign towards learning codes that approach the finite-length information-theoretic bounds.

For further details, we encourage you to review our paper.

References

[1] DeepPolar: Inventing Nonlinear Large-Kernel Polar Codes via Deep Learning, Ashwin Hebbar, Sravan Kumar Ankireddy, Hyeji Kim, Sewoong Oh, Pramod Viswanath. ICML 2024

[2] Turbo Autoencoder: Deep learning based channel codes for point-to-point communication channels, Yihan Jiang, Hyeji Kim, Himanshu Asnani, Sreeram Kannan, Sewoong Oh, Pramod Viswanath. NeuRIPS 2019

[3] KO codes: Inventing Nonlinear Encoding and Decoding for Reliable Wireless Communication via Deep-learning, Ashok Vardhan Makkuva, Xiyang Liu, Mohammad Vahid Jamali, Hessam Mahdavifar, Sewoong Oh, Pramod Viswanath. ICML 2021

[4] ProductAE: Toward Training Larger Channel Codes based on Neural Product Codes, Mohammad Vahid Jamali, Hamid Saber, Homayoon Hatami, Jung Hyun Bae. ICC 2022