In the previous post, we saw how model-based machine learning can help in boosting the performance of Turbo decoders. In this post, we apply the same principles to improve the min-sum decoders.

Channel coding

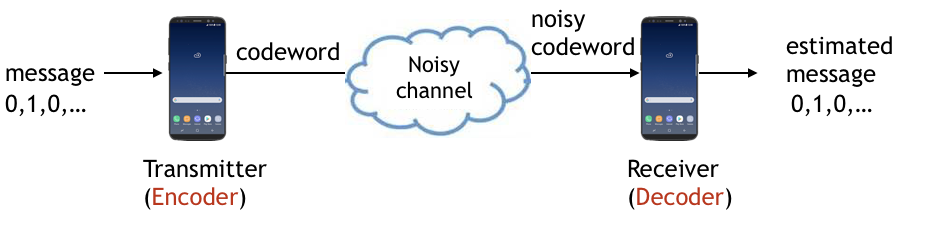

Consider communicating a message over a noisy channel. This communication system has an encoder that maps messages (e.g., bit sequences) to codewords, typically of longer lengths, and a decoder that maps noisy codewords to the estimate of messages. This is illustrated below.

Linear block codes and Tanner graph

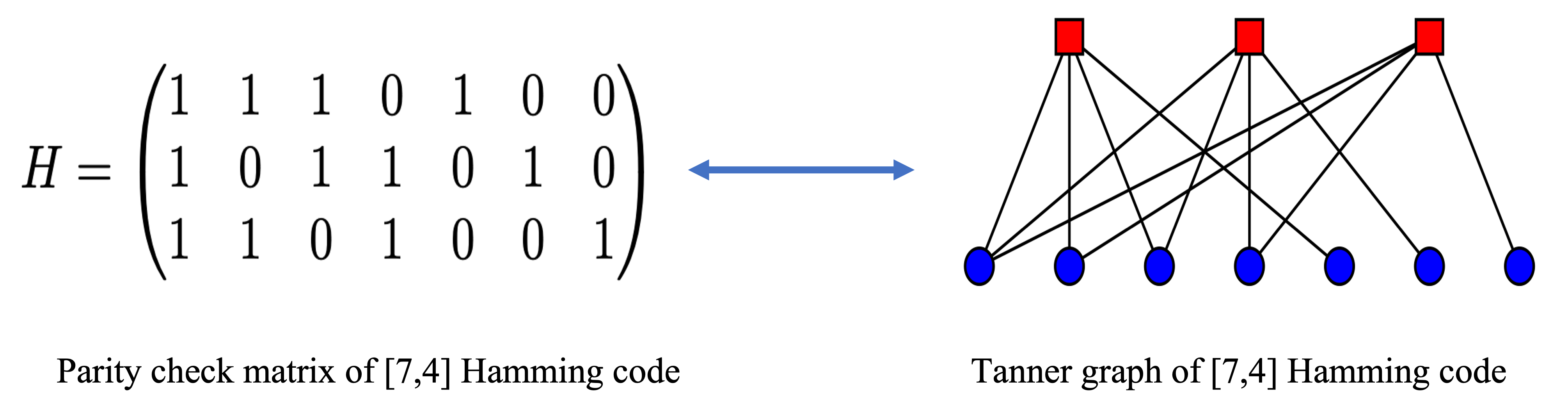

A \((N,K)\) block code maps a message of length \(K\) to a codeword of length \(N\) and is uniquely described by its parity check matrix \(\mathbb{H}\) of dimensions \((N-K) \times N\), where the rate of the code is \(R=\sfrac{K}{N}\). The linear block code can be also represented using a bipartite graph, known as Tanner graph, which can be constructed using its parity check matrix \(\mathbb{H}\). The Tanner graph consists of two types of nodes. We refer to them as Check Nodes (CN) that represent the parity check equations and Variable Nodes (VN) that represent the symbols in the codeword. There is an edge present between a check node \(c\) and variable node \(v\) if \(\mathbb{H}(c,v) = 1\).

Decoding of linear block codes

One of the popular choices for decoding of linear block codes is Belief propagation (BP), which is an iterative soft-in soft-out decoder that operates on the Tanner graph to compute the posterior LLRs of the received vector, also referred to as beliefs. In each iteration, the check nodes and the variable nodes process the information to update the beliefs passed along the edge. Operating in such an iterative fashion allows for incremental improvement in the estimated posteriors.

During the first half of iteration \(t\), at the VN \(v\), the received channel LLR \(l_v\) is combined with the remaining beliefs \(\mu^{t-1}_{c',v}\) from check node to calculate a new updated belief, to be passed to the check nodes in next iteration. Hence, the message from VN \(v\) to CN \(c\) at iteration \(t\) can be computed as

\[\mu^t_{v,c} = l_v + \sum_{c' \in N(v) \setminus c} \mu^{t-1}_{c',v},\]where \(M(c) \setminus v\) is the set of all variable nodes connected to check node \(c\) except \(v\).

During the latter half of the iteration \(t\), at the CN \(c\), the message from the CN to any VN is calculated based on the criterion that the incoming beliefs \(\mu^t_{v',c}\) at any check node should always satisfy the parity constraint. The message from CN \(c\) to VN \(v\) at iteration \(t\) is given by

\[\mu^t_{c,v} = 2 \tanh^{-1} \left( \prod_{v' \in M(c) \setminus v} \text{tanh} \left( \frac{\mu^t_{v',c}}{2} \right) \right).\]where \(N(v)\setminus c\) is the set of all check nodes connected to variable node \(v\) except \(c\).

Because of the inverse tan-hyperbolic functions involved, BP is over computationally intensive. Hence, a hardware-friendly approximation of BP known as min-sum is oftern used in practice. The approximated update equation for min-sum algorithm is given by

\[\mu^t_{c,v} = \min_{v' \in M(c) \setminus v} ( |\mu^t_{v',c}|) \prod_{v' \in M(c) \setminus v} \text{sign} \left(\mu^t_{v',c} \right).\]Suboptimality of min-sum decoding

While the min-sum approximation simplifies the computation, it also comes with a loss in performance. Because of the loss of accurary in the update at check node, min-sum decoder often performs poorer than the BP decoder.

Additionally, while BP is proven to be optimal on a cycle free graph, it’s performance is sub-optimal on graphs with cycles. The Tanner graphs corresponding to the linear block codes used in practice often contain short cycles, greatly hindering the convergence of BP decoder and reducing the error correction capabilities.

To address the above two reasons, correction factors such as offsetting and scaling the LLR values are often used in practice. Despite empirical success, there are no principled ways to find the optimal correction factors for a given tanner graph.

Finding the best correction factors

Model-based augmentation of decoders is perfectly suited for this scenario, by posing the search of optimal parameters as an optimaztion problem solved using Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD). The modified update equation at check node is thus given by

\[\mu^t_{c,v} = \alpha^t_{v',c} \left( \text{max}\left( \min_{v' \in M(c) \setminus v} ( |\mu^t_{v',c}|) - \beta^t_{v',c},0 \right) \right) \prod_{v' \in M(c) \setminus v} \text{sign} \left(\mu^t_{v',c} \right).\]where, where the coefficients \(\alpha_{v',c}^t\) and \(\beta_{v',c}^t\) denote trainable weights.

We refer to this as Neural Augmented Min-Sum (NAMS) decoder, also called neural min-sum decoder.

Adaptivity of learned parameters

We explain the improvement of neural min-sum decoders over classical decoders in a 2 phase manner. The first is the improvement due to offsetting the effect of cycles. This improvement is robust to variations in channel conditions. Te second is the improvement due to further correction of residual channel effects. This gain, of course, depends on channel conditions.

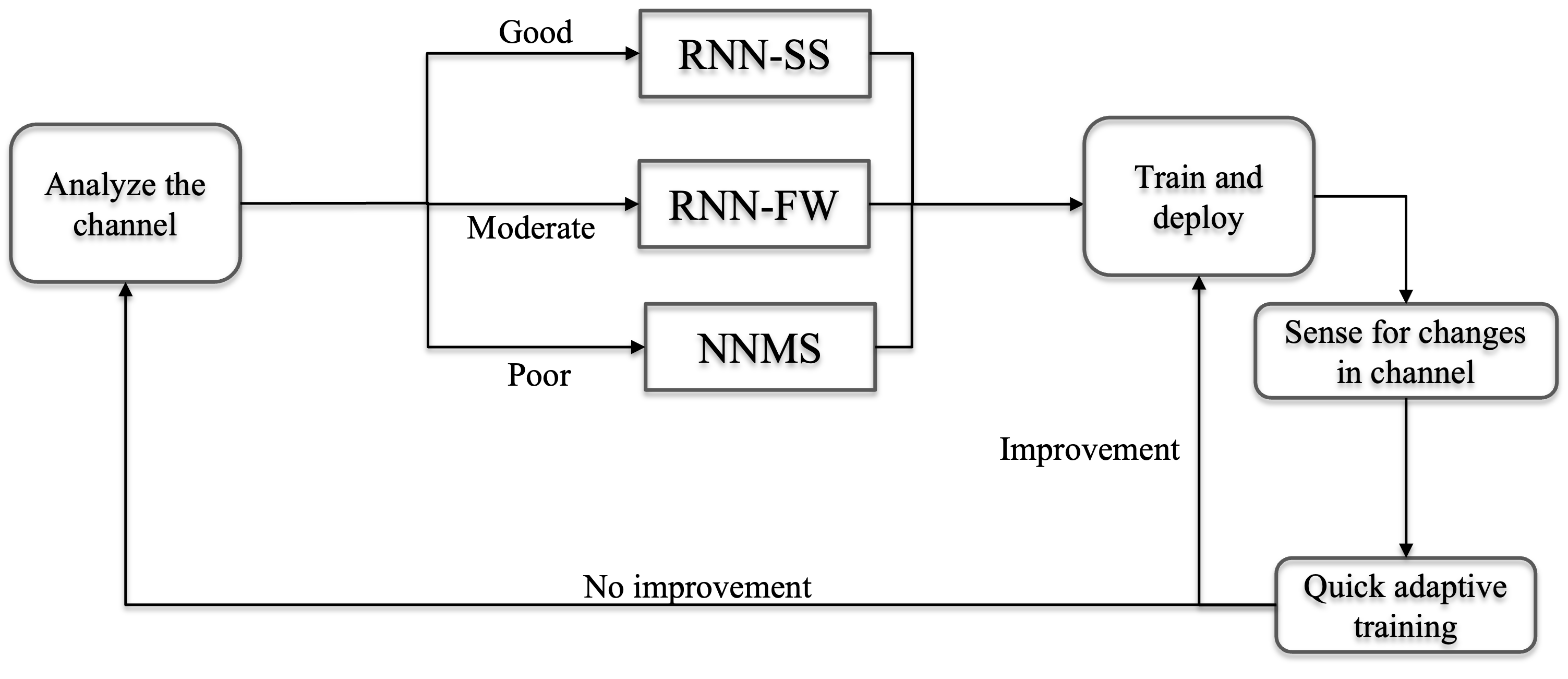

Since the channel conditions can vary often in practice, we desire the model to be robust as well as easily adaptable to these variations. We propose the following dynamic model for parameter selection as follows

NAMS codebase

We provide a framework in Python to implement and evaluate different neural min-sum decoders, and implement model-based ML methods like NAMS. The project repository and running instructions can be found here. Further, we provide an intuitive interface for inference and training of NAMS in the deepcommpy package.

The code snippet below demonstrates how to use this package for Neural Min-Sum code decoding inference for BCH code, block length 63:

import torch

import deepcommpy

from deepcommpy.utils import snr_db2sigma

from deepcommpy.channel import Channel

# Create a Linear Block code object : BCH (63,36)

message_len = 36

block_len = 63

rate = 36/63

linear_code = deepcommpy.nams.LinearCode(code='bch', message_len = message_len, block_len = block_len)

# Create an AWGN channel object.

# Channel supports the following channels: 'awgn', 'fading', 't-dist', 'radar'

# It also supports 'EPA', 'EVA', 'ETU' with matlab dependency.

channel = Channel('awgn')

# Generate random message bits for testing

message_bits = torch.randint(0, 2, (10000, message_len), dtype=torch.float)

# Encoding

coded = nams.encode(message_bits)

# Simulate over range of SNRs

snr_range = [-1.5, -1, -0.5, 0, 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2]

for snr in snr_range:

sigma = snr_dbsigma(snr)

# add noise

noisy_coded = channel.corrupt_signal(coded, sigma)

received_llrs = 2*noisy_coded/sigma**2

# NAMS decoding with 6 iterations

_, decoded = nams.nams_decode(received_llrs, number_iterations = 6)

# Compute the bit error rates

ber = torch.ne(message_bits, decoded).float().mean().item()Results

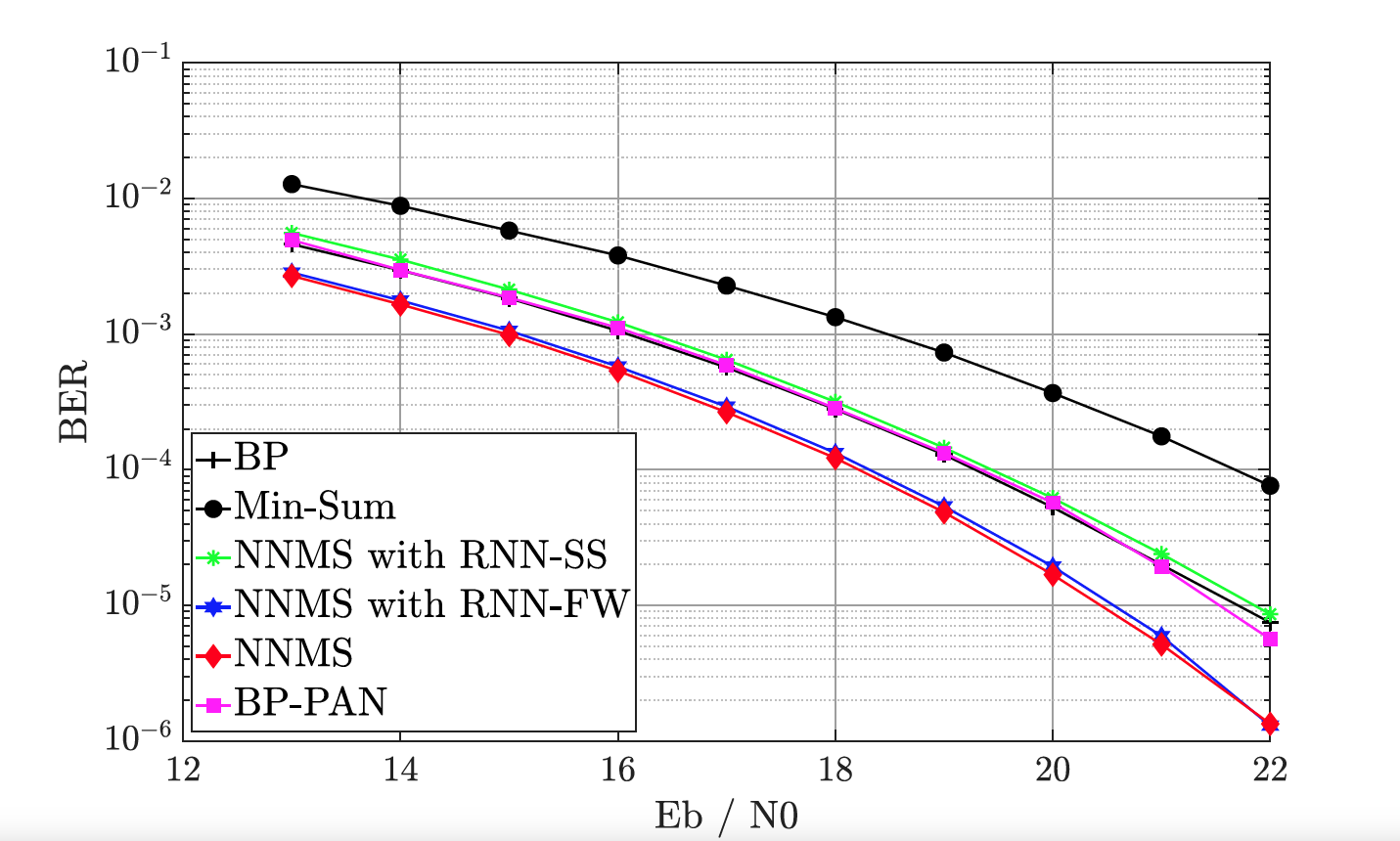

The gains in decoding performance due to neural augmentation depend on two factors. The first is the amount of short cycles in the code and the later is the complexity of the channel.

In the following figure, we consider BCH (63,36) and Extended Typical Urban (ETU) channel model, which consists of high multi-path components further degrading the quality of LLRs. We see that the high parameter model of neural min-sum decoder improves the decoding performance of neural min-sum decoder by more than 3.5 dB.

References

Interpreting Neural Min-Sum Decoders, Sravan Kumar Ankireddy, Hyeji Kim. International Conference on Communications (ICC), 2023.